The GRE is Dystopian

It's also way too easy.

I’ve been applying to graduate schools recently, and as part of this process, I chose to take the GRE, or Graduate Record Examinations.

For my whole childhood, I built up an internal image of the GRE as a Big, Scary Test: the bugbear of scholarly young adults, the eater of graduate school dreams everywhere. The reality turned out to be much different— and much more dystopian— than I had imagined.

However, before I can begin that story, I first need to introduce its central character. The ETS (Educational Testing Service) is a private US nonprofit founded in 1947. You may know them from such heavy hitters as the TOEFL for assessing English ability for non-natives, the PSAT for young high schoolers, and the CLEP for extra college credit.

In the United States, the SAT measures apparent ability for American undergraduate prospects, and the GRE is its graduate school counterpart. Also like the SAT, the GRE has a written essay section, a grammar section, a reading comprehension section, and two quantitative sections.

The GRE exists to be a single yardstick schools can measure applicants against. GPA is insufficient because it varies so much from college to college. On the one hand, the Ivy Leagues inflate their grades so much that an A has little meaning. On the other, schools like MIT and the University of Michigan are as cold as the states that host them, and in many of their classes, a C is an impressive grade.

I completely support the idea behind the GRE. I just wish the implementation wasn’t so easy.

Seriously, despite what you might have heard, the GRE is trivial. It’s no more difficult than the SAT, despite being meant for students who are four years older and on the other side of an entire undergraduate education!

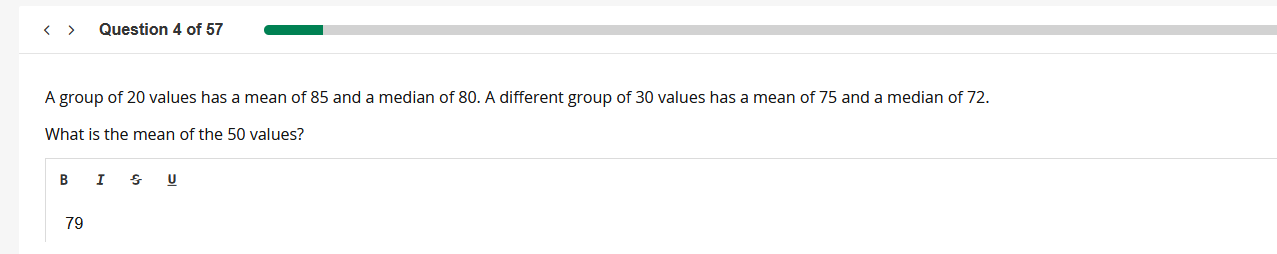

The following question, which is from ETS’ official practice service, is typical:

This is a effectively an SAT question. To solve it, you just need to know how to calculate a mean. This is not something you need to go to college to know how to do!

I am frustrated by the GRE’s sheer triviality. It does not test a single college-level subject— not calculus, not anatomy, not biology or philosophy or language or vector analysis or programming or ANYTHING! This is particularly embarrassing when you compare our tests with those of any other advanced country. Take a look at the German Abitur, for example, where students get to perform calculus on vectors in three dimensions to solve problems. Or test your mettle against the Chinese Gaokao, with its own biology section asking students to decode complex diagrams. Meanwhile, the only way for an American to get tested in biology at the graduate level was to take a separate test, and even this door was closed in 2021.

The cancellation of the Biology GRE is part of a pattern whipping across American assessment. America has always had the weakest examination culture of any developed country. The atrophy of this culture accelerated after the 2020s, as the pandemic forced the test online and universities suspended testing requirements. These suspensions found a way of becoming permanent.

The result is that, while the GRE used to be a standard requirement, nowadays the proportion of schools that require it is falling precipitously. In my experience, those that still require it are often middling schools, those that are neither the worst nor the best in their state. For them, GRE scores may provide a useful differentiating factor among students who may not have uniformly excellent GPAs. However, its use among top schools is all but done, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the GRE itself ceases to exist in a few years.

Vocabulary: The Funnest Part of the GRE

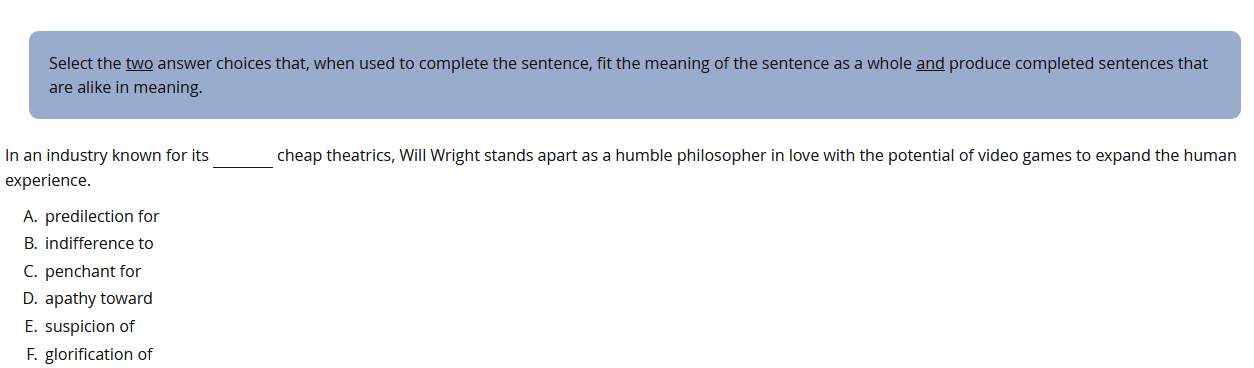

While so far I have mostly been complaining about the GRE’s stultifying similarity to the SAT, there is one rather infamous point of divergence. The GRE asks for advanced knowledge of English vocabulary, and it does so in an oblique and, honestly, very creative way.

The example above is a sentence equivalence question. I like it because it asks you which two words are near-synonyms in a functional way— that is, in the context of the rest of the sentence. This represents how language truly works. Dictionaries are glories of our civilization and beauties of scholarship. But they obscure the full dimension of signification, which grows only when a word is dropped into the full context of its phrase, sentence, chapter, and speech community.

I found these questions a lot of fun, though it probably helps that I already knew the majority of GRE-tested words. For the ones I didn’t, I used Vince’s vocab list (link), loaded the words I didn’t know into Anki, and studied with celerity until the day of the test and after. This helped me get back into the habit of regular Anki repetitions, so thank you GRE for that, I guess. This was, for me, the GRE’s best feature.

A Dark Chill

Some criticisms of the GRE are, in my opinion, well-said. For example, the fee to take the test is a ridiculously large $220. I was shocked by this number at first— while proctoring isn’t free, $220 seems exorbitant, especially in comparison with the $68 SAT fee.

The sky-high fee hurts poorer students. Back when the GRE was required for nearly all graduate admissions at American universities, the sky-high fee led to a severe economic barrier to entry for students to even try to improve their station in life through graduate study. This no doubt has also led to psychological barriers for these students.

All this being said, there is a reason for the sky-high fee. I discovered it when I came to take the test.

The sinister aspect of the test gets even worse. At the same time that it’s selling the test for a high fee, the ETS also sells tons of very high-cost practice materials for it. This seems like obvious grifting: they simultaneously sell a gate to entry and the keys to unlock it, both at very high cost. Students who use official ETS study resources are at a major advantage. It all makes the GRE feel less like a disinterested evaluation of capabilities and more like an opportunity for ETS to line its pockets.

The Testing Experience

To its credit, the ETS offers very frequent test dates, and I was able to schedule a date pretty much exactly to my liking. I decided to schedule a very early date, because I needed the score by a looming deadline, and I wanted to be done before the MIT Mystery Hunt [link]. As a result, I only gave myself about two weeks to study, and only seriously studied for a few days. So irresponsible!

There are two ways to take the GRE: an online exam and an in-person exam. The receiving schools can tell which version of the test you took, so rather than have them think I might have cheated, I chose the in-person exam. This involved driving a few miles to the nearest testing center in Longmont.

I took the test in an independent private test center in a strip mall. I paid them no money: presumably they get a (large?) cut of the testing fee.

This is when I learned why the testing fee is so high. The amount of security at the center rivaled the TSA. They emptied my pockets. They waved a metal detector over me. They took off my glasses and gave them a 360-degree inspection. It turns out that it’s much easier to cheat in grad school than in applying to grad school.

Next, I plopped down into my assigned cubby and donned a pair of headphones. If I wanted to use the bathroom I had to exit and, upon reentry, be scanned once again. A water bottle was not allowed, nor was, of course, anything in my pockets. It is by far the most secure test I have ever taken.

The exam itself, as I have already said, was trivial. I was given on the writing section a prompt about whether modern technology impedes the development of morals, to which I answered no, because I believe the development of the human virtues is possible in a wide variety of conditions (perhaps all conditions). I got to cite Nicomachean Ethics in my response… my reading of it in high school in an attic in the mountains apparently paid off.

A few weeks later, I got my score back. I did very well and received no penalty for my foolish lack of study. One interesting observation is that my scores in the quantitative and in the verbal sections were similar, but the percentile in the quantitative section was much lower— just 76th as opposed to 99th for the verbal section. You can confirm this yourself if you look at the score percentiles for each section.

Why does the quantitative section have such a higher mean than the verbal? My guess is that it’s because of selection effects on the kind of student who takes the GRE. Students with a quantitative tilt might be more likely to take the GRE because engineering and STEM-oriented programs are more likely to require it than, for example, creative writing programs. As a result, GRE test-takers tend to be better at quantitative reasoning, and so the average score on the quantitative reasoning section is higher.

Does it Accurately Predict Graduate School Performance?

While the SAT has been shown to accurately predict college success, it appears prima facie that the GRE will not be as good just because it’s too darn easy. I struggle to see how an exam that only tests high school-level concepts can differentiate one college graduate from the other.

To what extent does the GRE actually predict performance in graduate school? The ETS, the most biased source possible, has published its own research indicating that the GRE does correlate strongly with graduate school success.

Other studies paint a less rosy picture. Quite a few studies and one meta-analysis have found only weak predictive power for the GRE.

That being said, I was able to find one recent study arguing that it was a strong predictor of various valued graduate student outcomes. The meta-analysis is, in my opinion, the best source, showing that the correlation between GRE and student grades has always been positive across various studies. It does, however, vary based on the department: interestingly, the correlation is highest in the humanities and the liberal arts.

Were I an admissions administrator, I would run a local study and determine correlation with GRE scores and preferred outcomes for historical grad students in my own department. However, even in the best predictive case, I would never let the score be anything more than one component of the equation. I think the GRE is best viewed as a lens through which to view more important components, like grades and recommendation letters.

All the same, I’m not an admissions administrator. Whether I like it or not, the winds of change are blowing against the GRE. I doubt my children or grandchildren will take it. Maybe that’s for the best.